The "Crown of the Continent"

"Far away in northwestern Montana, hidden from view by clustering mountain-peaks, lies an unmapped corner-- the Crown of the Continent."

George Bird Grinnell, often called the "Father" of Glacier National Park, wrote those words in 1901. Looking up inside the Park one is struck from all directions by finely-etched peaks and razor-sharp escarpments; the golden points of American regalia.

Glacier is unanimously recognized as a crown jewel of both national and international biosphere preserves. Yet it remains, as it was a hundred years ago, largely uncharted. The 1.2 million-acre Park has been surveyed, its topography mapped and remapped, but notions of longitude, latitude, and even time haven't quite taken hold in the high country.

Changing seasons and geologic patterns still govern life's activity there. Ticking hands of the clock are silenced. Other than the few townsites scattered along its borders and a couple of alpine chalets, the only substantial evidence of human activity in the region is a 52-mile road running east to west and roughly bisecting links of the Park's mountain chains.

How the Mountain Got Its Name

Sometime during the mid 1880's James Willard Schultz, a writer who first convinced George Bird Grinnell to visit the area, was out on Red Eagle Mountain with Tail-Feathers-Coming-in-Sight-Over-the-Hill. The two were butchering a ram together.

Tail Feathers suggested that the peak would make an ideal spot for a vision quest. The two talked it over and arrived at the English, "Going-to-the-Sun Mountain." As understood here, the vision quest entails a certain sacrifice. The physical burden of the journey and its accompanying loss of ego serve to rejuvenate the mind, body, and soul.

A Story of Sacrifice

The story of Going-to-the-Sun Road is a story of sacrifice. People sacrificed ancient hunting grounds. Now they are preserved and protected.

Others worked for years to survey and construct the road. A few of them lost their lives to the project. Efforts early in this century made the Park accessible to millions who, otherwise, could only have guessed at the wonders within.

Early Explorers in the Mountains

Although French and English explorers crisscrossed these mountains throughout the 18th century, David Thompson is credited as the first European to record his impressions. In the late 1780's he wrote of the peaks, "Their immense masses of snow appeared above the clouds and formed an impassable barrier even to the eagle."

Thompson's eagles once thrived amongst Glacier's mountains and valleys. Goats navigate high narrow ledges with the grace of slippered toes. The author imagines Thompson himself even venturing out once or twice across what the Blackfoot have called "the backbone of the world."

When Capt. Merriweather Lewis set out to explore the Marias River in 1806, he fell just short of the present-day Park. Weather prevented Lewis and his men from seeing what lay to their north, but Going-to-the-Sun Road now cuts through the Lewis Range, named in the explorer's honor.

Schultz and Grinnell Discover Glacier

James Willard Schultz, a full member of one Blackfoot tribe, finally succeeded in attracting George Bird Grinnell, an east-coast writer and publisher, to the area in 1885. Grinnell had traveled extensively through the West, even accompanying Custer's Black Hills expedition in 1874 as a naturalist.

Grinnell arrived at Schultz's camp with just a canvas-covered bedroll, a war sack, a Sharps .45 caliber rifle, and a fly-rod; appropriate gear for the time. George Bird returned to the area for each of the next nineteen years, until prevented by illness. Schultz and Grinnell climbed and hunted on many mountains during their time together.

Getting People To and Through Glacier

Glacier's inception created two obstacles for Park planners. The first was bringing people to Glacier. The next, and more difficult problem, was moving them through Glacier.

Jim Hill answered the first troubling question. Hill's Empire Builder route over Marias Pass led to the establishment of Midvale and Belton (now East and West Glacier, respectively). The year was 1910. The era of the railway, as passenger transport, was nearing the end of its line in this country. The United States motored along through open country, right on into the era of the automobile.

Transcontinental highway projects sprang up as auto-touring clubs came into vogue. While roads existed, more or less, to and from Belton and Midvale, none connected the east and west sides of the Park with one another.

Motorists hoping to cross the Divide faced two options. They could either load their car onto one of Hill's railcars and tag along for the ride, or else drive as far south as Butte or Helena to the nearest road across the Continental Divide; a one-way journey of around 200 to 250 miles. Either way, the trip was cumbersome, costly, and avoided by most. Today a road parallels the tracks over Marias Pass, skirting the southern border of the Park, but missing most of its majesty.

Early Park Plans and Road Debates

Major William R. Logan arrived in the new Park toward the end of summer, 1910, and was appointed its first Superintendent in spring of the following year. Soon after his arrival, Logan was looking to lay a road through Glacier's backcountry.

At that time, travel inside the Park usually meant guided, multi-day, horseback trips. The Pack Horse Saddle Co. in Glacier was thought to be the largest operator of its kind on the continent. But a guided pack trip into remote tent camps and high-country chalets was an adventure few Americans could afford.

Park administrators had another concern: They understood that lack of communication between east and west would slow development and stunt action during times of emergency.

In 1910 fevered debate still raged within the Department of the Interior on the question of whether to allow roads inside National Park boundaries. But by 1911 it seemed fairly clear, at least within influential circles of Park management, that they would build a road through Glacier. Park officials were confident that a road could be put down. The only question was where it would lead.

The First Roads Near the Park

As of 1911, the closest road to Glacier from the west ended in Coram, a long eight miles outside Belton. In May of that year Frank Stoop drove his E-M-F "30" up the old Great Northern railway tote road and pulled into Belton nine hours later. He kept a pace of less than one mile per hour.

By the end of that summer Flathead County had improved the road so that visitors could bring their autos to the gates of Glacier. Urged on by this local enthusiasm, the Department of the Interior dispatched T. Warren Allen, locating engineer with the Bureau of Public Roads, in 1914 to evaluate the feasibility of Marshall's plan.

That same year a road linked Midvale (East Glacier) with the nation's highway system. The original suggestion for a route over Jefferson Pass had already been changed, in favor of Brown's Pass.

Allen soon ruled out Swiftcurrent and Gunsight Passes as unsuitable for an east-west crossing and indeed, looking down from those passes today, one wonders what Mr. Marshall could have been thinking. Allen found potential in both Brown's Pass and Logan Pass. He also tacked on Piegan Pass as a possibility, but retained the Belton-Waterton route as the centerpiece of Glacier's proposed road system.

By this time, west-side communities felt that Park planning over-emphasized Jim Hill's east-side developments. Community spokespersons were convinced that a north-south route, as Glacier's primary byway, would pass right over their future interests.

The First Inside-the-Park Road

The only road inside the Park back then was a washed out wagon trail connecting Belton to the small town of Apgar, at the foot of Lake McDonald. It was described at the time as, "a combination of quagmire, corduroy, and misery; the worst three miles in the State of Montana."

Though none of those three miles are a part of today's Going-to-the-Sun Road, improving that stretch became the first impetus for its construction.

Local Pressure and New Ideas

Merchants clamored for officials to rethink the Park's future and to restructure its possible scenarios. P.N. Bernard, Secretary of the Kalispell Chamber of Commerce, went so far as to claim that: "A Park without roads is a menace to civilization and settlement and a barrier to communication between states and districts."

Flathead Valley residents drew up a proposal of their own with a new road traversing the west shore of Lake McDonald and crossing the Divide by way of Gunsight Pass. They recruited Dr. Lyman Sperry, long-time advocate for Glacier's west side, to speak on their behalf.

Sperry accepted, though he was forced to admit that the Gunsight route would require, "a number of interesting-- but not forbidding-- stunts in engineering and autoing." That proposal eventually died, but the argument was heard.

Stephen Mather and Big Decisions

During the first fall snowstorm of 1915, Stephen Mather (who became the first Director of the National Park Service in 1916) and his assistant Horace Albright (who later succeeded Mather) made a horseback trip over Gunsight Pass at the request of area residents.

Mather rejected the Marshall plan completely, convinced that one and only one road should encroach upon each park. Though he felt committed to the idea of an east-west crossing, Mather also abandoned the Gunsight proposal after concluding that the extreme difficulty of laying a road across Gunsight Pass would render the effort ridiculously cost-prohibitive.

Choosing the Logan Pass Route

The only recommendation never dropped from original Park plans was for a road leading from Belton, along Lake McDonald, over Logan Pass, and dropping into the St. Mary Valley. This route seemed to fulfill all significant concerns while allowing visitors sufficient access to Glacier's stunning high country from the comfort of their own cars.

The route was surveyed and, finally, the first vexing problem set appeared solved. The next issue took a more pragmatic scope; Park Administrators still had to pay for what was arguably the most challenging road ever constructed in United States history.

Early Funding and Slow Progress

In those years, large National Park projects were denied funding almost systematically. That situation was no different in the case of the "Transmountain Highway," as it was first known. World War I swiftly ended any thoughts that the project might soon proceed.

But after the war, things picked up again. A $12,000 appropriation by Congress in 1920 allowed for the construction of a new arch bridge spanning the Middle Fork of the Flathead River at Belton.

The following year Glacier received $100,000 to build a road from Apgar to the head of Lake McDonald. These were the first in a ten-year stretch of appropriations funding construction of the Transmountain Highway.

Building Along Lake McDonald

After clearing right-of-way for the road along the east shore of Lake McDonald, the Park Service let all subsequent work out to private contract. In August of 1922 cars from the Flathead Valley were allowed to drive about a third of the way up the Lake.

Area residents had kept a close eye on progress and over 200 cars made the journey that first day. Before the lakeshore section was even complete, a $65,000 appropriation fueled another project from the head of the Lake up to Avalanche Creek.

The next year Glacier received funds to begin some east-side construction. Work there was to begin at the St. Mary Chalets (at the foot of St. Mary Lake) and proceed toward Going-to-the-Sun Chalets (at Sun Point), as far as $100,000 could take it.

The Challenge of Crossing the Divide

At this point Transmountain Highway had just about reached its practical ends. Although most everyone involved was in favor of the Divide crossing, and the project was nearly fifteen years along, laying the road was clearly going to be a monumental feat; an effort without precedent in this country.

During the 1920's, as cars were being sold on credit across the country, the United States was spending over one billion dollars annually on highway construction and maintenance.

Frank Kittredge Finds a Better Route

In 1924, the House Committee on Public Lands set aside $1,000,000 for further construction of the Transmountain Highway. Now people began to question the 1918 Parks survey of the Logan Pass route.

That survey had staked out a road crossing Logan Creek seven times, making eleven hairpin turns, and ascending the Divide at up to eight-percent grades. The road would then have dropped sharply into the St. Mary Valley making just two switchbacks.

For much of the way, Glacier's scenery would have remained concealed from view and, furthermore, the road would be taxing to drive, difficult to maintain, subject to large snow accumulation over the winter and virtually impossible to improve at a later time.

In September of that year, the Bureau of Public Roads sent Frank Kittredge to survey an alternate route. With just over a month remaining before winter, Kittredge kept 32 men on the job at all times in order to complete the task.

The work was difficult and dangerous. Few men stayed long on the job. As he later said, "There were really three crews; one coming, one working, and one going." Nevertheless, Kittredge established a new route and the decision was made to concentrate all funds and efforts on the 12.5 mile stretch following McDonald Creek and leading over Logan Pass.

Hard Work in a Hard Place

Until 1925, progress on the Sun Road operated under less-than-favorable conditions. But that was true throughout the West. Roads were still scarce and equipment was crude.

Construction of Going-to-the-Sun Road, building a 12.5 mile western stretch and an additional 10.5 miles on the eastern slope, is described as a tale of sheer will. The Logan Pass route was never clearly visible. It was not an obvious choice.

Glacier rarely reveals anything like an obvious choice. Many mountaineers have been turned away from a new summit by impending darkness after spending the afternoon searching out a safe path.

It was right for road-planners not to begin work without a clear idea how to finish it. The road spent a full fifteen years in "research and development" and another eight under construction. Sun Road pioneers surely understood the first lesson of the mountains: There is always another day.

Bids, Contractors, and Camps

That day came on June 10, 1925, when bids opened in Portland, Oregon for the west-side haul up to Logan Pass. Bureau of Public Roads officials invited contractors to see for themselves, firsthand, the job on which they were about to bid.

The Bureau and the Park Service set up a special camp and for four days 35 contractors traversed the Garden Wall, crossing steep snowfields just to get a look at the site. They spent two full days roped together in the rain.

Williams & Douglas of Tacoma submitted the low bid at $869,145. A month later, Williams & Douglas had their crews out on the site along with BPR project engineer W.G. Peters and his men.

Headquarters was located at Camp 1 near Logan Creek and a series of five more camps was eventually established along the route. Williams & Douglas were obligated to fulfill the contract by October 1, 1928.

Tools, Labor, and Daily Life

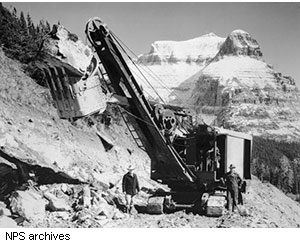

At its high point, the project employed about 300 men. They blew 250 tons of explosives in excavation, just less than one pound per cubic yard. It often took six men with six big crowbars to move the two-ton boulders.

Station gangs were paid by the cubic yard of material moved, which came out to around $1.15 per hour; good wages back then. In addition to strong muscles, they used four three-ton gas locomotives with twelve two-yard dump cars and 3,000 feet of 24-inch gauge track, six portable compressors, one Fordson tractor, two graders, and an assortment of trucks, teams, and wagons.

The work season was 200 days per year at best and snow was removed from camps and road by hand each spring.

Hanging on the Garden Wall

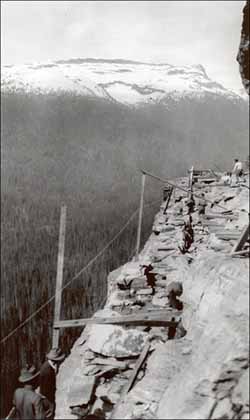

The Garden Wall, a shale rock face from which the Sun Road was carved, is a long steep slope eventually rising to sheer cliffs some 1000 vertical feet above the road-cut. The extreme nature of the surrounding environment often forced survey and construction crews to hang suspended from old hemp ropes.

These men weren't skilled mountaineers. Many of them had probably never seen anything on the order of Glacier's wilderness. Being thrown into the high country for days on end (one former laborer recalled working 21 hours a day for more than a month) must have been a thrill, and an absolute terror at first.

Demands of the job kept the men focused though. Ernest Johnson earned forty cents an hour working the rock crusher for A.R. Douglas: "Boy he really worked you too. He would follow you over to get a drink of water and made sure you came back quick."

The men would stay in camp for two or three weeks at a time (with no shower). They paid a dollar a day for room and board and were kept pacified with a full stomach. Russell Munter said, "If the food wasn't any good, they had a new cook in the morning. By God, we had good grub."

Bears in Camp

The good grub attracted more than just some sweaty workers coming off of a long shift. Local bears soon caught up with the daily feasts given in their backyard.

Each cook handled the bears in his or her own way. Some hung their supplies high in the trees. Others put up nails in the doors and built a drawbridge to get inside. A few reportedly resorted to more "explosive" tactics.

Friendly cooks just fed them flapjacks in the morning, though Park Rangers eventually discouraged that practice. One cook up and ran away, never seen again around camp.

Doris Huffine remembers, "She was alone there all day but one day the bears got to be too much. Her work table was up against the side of a tent, and she was making pies, when all of a sudden a great big black bear paw tore through the side of the tent to get at the pastry."

Another camp cook, Dorothy Price, named all the bears around her tent. There was Jean and Brownie, Amos and Andy, and Nip and Tuck. Crafty clearing crews laid cross-cut saws near the trees where they kept their lunches to keep the bears at bay.

Apparently, grizzlies kept to themselves most of the time. A few workers escaped the worries of camp life by venturing down to the Saturday night dances in Apgar.

Dynamite, Rockslides, and Danger

Bears were only a minor concern. Gravity and dynamite posed more immediate threats. Workmen covered their hobnailed boots with heavy wool socks to prevent accidental sparks from igniting explosive powder.

Joe Opalka witnessed a planned blast at one precarious corner: "Those old-time powder monkeys really knew what they were doing. I packed powder in there [Camp 4] for three weeks, and the powder monkey said they were going to blast the whole thing in one shot. He said when it went, the road would be right through."

He remembered, "He hollered 'fire,' and that whole hillside gave a little thud, with the black powder, then the rock powder went off and the whole thing just moved into the canyon. It was quite a rumble, but not too much noise. You could have drove a truck through it when the blast was done. It was just like a finished road-bed."

He added that, "They made a little mistake on that lower end of the tunnel. Somebody put too much powder in and they shot part of it off." Road crews were in constant danger from rockslides. Reverberations from air hammers could be heard for sixty miles and, during some phases of construction, at almost any time of day.

Reaching the Pass in 1928

The western leg of the Transmountain Highway finally reached Logan Pass on October 20, 1928, just 20 days later than specified by the Williams & Douglas contract. The delay, however, was due to an expansion of the contract to improve some previously completed sections of road.

Otherwise, the work had proceeded right on track. The Sun Road claimed one life during those three seasons of construction. Charles Rudberg fell sixty feet after losing his grip on a rope about one mile above The Loop.

As tragic as even this single death is, it is described as testimony to the dedication of everyone involved that so many lives were preserved under such hazardous conditions. The new road, built to the highest of contemporary standards, was opened to car traffic on June 15, 1929. That year alone, Glacier saw a 46% increase in automobile visitation.

Building the East Side

Another two years went by before construction began in earnest on the eastern section of the road. By then, the name "Transmountain Highway" had given way to "Going-to-the-Sun Road," after briefly being known as the "Logan Pass Road."

Two separate bids were let for the east-side phase, one as far as Sun Point and one up to the Pass. A.R. Douglas (formerly in charge of west-side work) was handed a subcontract for the central portion.

Faced once again with the task of building a road while having no access for equipment, Douglas ordered built two 60-ton capacity pontoons, lashed them together, and used this barge to float his power shovels and other gear to the head of St. Mary Lake.

A 1,000-foot tote road from the lake to the roadcut was the only supply route used during his stint around Sun Point.

Tunnel Building on the East Side

Colonial Building Co. of Spokane was given responsibility for the most challenging section on the east side; a 408-foot tunnel two miles below the Pass. Workers excavated 6,250 yards of material just to open up a safe "bench" before working on the tunnel.

All supplies were then hauled down a 100-foot trail lying at nearly a 45-degree angle. A.V. Emery, engineer in charge, expected that a man in good physical condition could carry a 50-pound box of dynamite down the trail and ladder in half an hour.

According to G. LaVerno-Harrison, "On several occasions men stood at the top of the cliff, looked down the ladder, and turned in their resignations."

Working 24 hours a day, on a three-crew rotation, Emery's men holed through the tunnel at 10:00 p.m. on October 19, 1931. Work was near complete when weather shut down operations for the season in 1932.

Two other workers met their fate during that last summer of work. A falling rock struck Carl Rosenquist near Logan Pass and stonemason Gust Swanson was also near the pass when he fell over 400 feet to his death. Since then, others have passed away while maintaining the road.

Finishing the Road and Its Design

The final touches were made on July 7, 1933 for a total cost of $1,700,000, though some additional work was already planned. With masonry guardrails constructed from the very same rock excavated for the roadbed, the Sun Road stands as a tribute not only to civil engineering, but to aesthetic regards as well.

Retaining walls blend into the hills and its contours snake in and out of view, making Going-to-the-Sun one of the least obtrusive paved roads around.

Dedication Day: July 15, 1933

Opening and dedication ceremonies were held on July 15, 1933. Glen Montgomery served up the largest meal ever cooked in Glacier to more than 4,000 visitors and motorists, though he'd only planned on a crowd of around 2,500.

Montgomery concocted a chili from 500 pounds of red chili beans, 125 pounds of hamburger meat, 100 pounds of onions, 36 gallons of tomatoes, and 15 pounds of chili powder, adding salt and pepper "until it tasted right."

He needed one assistant to stir the nine copper-bottom wash basins full of chili and two more to constantly stoke four wood-stove fires. Others kept fires burning at the Pass to keep the chili hot. They started hauling it up there a full twelve hours before ceremonies began.

Even with twelve extra cases as backup, the chili didn't quite go around. But there were hot dogs and coffee and most everyone was fed something. Glen, the cook, slept through the ceremonies.

Speeches and Celebration

Photographs from that July day reveal sun-drenched smiles and an air of relief. Those in attendance celebrated more than 20 years of planning and construction.

O.S. Warden unveiled a plaque in memory of Stephen Mather and spoke on Mather's role in National Park development. Other speakers included W.A. Buchanan of the Canadian Parliament, A.V. Every from the Bureau of Public Roads, Senator Burton Wheeler from Montana, and Frank Cooney, Governor of Montana.

Someone even assembled a few fresh CCC recruits to form an impromptu boys' choir. The cars of enthusiastic park-goers were creatively parked amidst the delicate alpine tundra of Logan Pass.

The scene represents an unusual juxtaposition of technological refinement and natural beauty, which has come to signify Going-to-the-Sun Road.

A Road, Its Legacy, and Peace

Horace Albright, director of the Park Service and the man who'd accompanied Mather on his early trips to Glacier, sent along a message ending with the simple request, "Let there be no competition of other roads with the Going-to-the-Sun Highway. It should stand supreme and alone."

Despite the realization of a monumental feat in engineering, the day's greatest achievement came, for many, when delegates from formerly hostile tribes of Blackfoot, Flathead, and Kootenai Indians gathered for a ceremonial offering of peace and passing of the pipe.