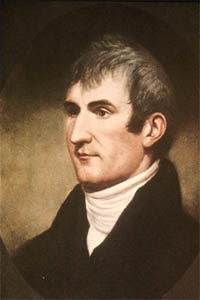

Meriwether Lewis

Updated: February 3, 2026

Meriwether Lewis was about 29 years old when he took command of the Corps of Discovery, the expedition that would become one of the most significant exploratory missions in United States history. President Thomas Jefferson chose Lewis in 1803 not only because he had served as Jefferson's private secretary since 1801, but also because of his frontier experience, military service as an army officer, and his demonstrated skill as an observer and record-keeper.

Although Lewis had limited formal schooling, recent scholarship emphasizes how carefully he prepared for the expedition with some of the leading scientists and physicians of his time. Before heading west, Lewis traveled to Philadelphia, where he studied astronomy and navigation with Andrew Ellicott and Robert Patterson, botany and zoology with Benjamin Smith Barton, anatomy with Caspar Wistar, and practical medicine with Dr. Benjamin Rush. These crash courses gave him the skills to take celestial observations for latitude and longitude, describe new plants and animals in detail, collect and preserve specimens, and treat illnesses and injuries among the Corps and the Indigenous communities they met. During the expedition, Lewis served as the principal field scientist, recording extensive notes on botany, zoology, geography, weather, and Native cultures that later became foundational sources for American science and western cartography.

Lewis's medical training under Benjamin Rush and other mentors, though brief by modern standards, proved valuable in the field. He dispensed medicines, performed minor surgical procedures, and used common treatments of the day such as purgatives, bloodletting, and "Rush's pills," often with mixed results by current medical standards but with enough success that members of the Corps generally survived disease and injury better than many other frontier parties. Expedition journals describe him treating a range of ailments-intestinal illnesses, infections, injuries from accidents, and more-and offering care to some Native people they encountered, reflecting both the limits and ambitions of early 19th-century medicine.

After returning in 1806, Lewis was appointed governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory (often called Louisiana Territory) and was expected to oversee a vast, complicated region while also editing his journals into a full, published account. Historians note that he struggled with the demands of territorial politics, conflicts with federal officials over accounts and funding, and the enormous task of organizing the expedition's scientific data for publication, all while facing growing financial problems and signs of depression. Although some manuscripts and maps moved forward with the help of other editors after his death, Lewis himself never completed the comprehensive multivolume narrative Jefferson had envisioned.

Meriwether Lewis died on October 11, 1809, at Grinder's Stand on the Natchez Trace in what is now Tennessee, at the age of 35, from two gunshot wounds. From the time of his death, people debated whether he had been murdered or had taken his own life; some family members and later writers favored a murder theory, while Thomas Jefferson, William Clark, and several contemporaries believed he died by suicide. Modern historical and medical analyses generally conclude that, although absolute proof is impossible, the weight of evidence-his earlier suicide attempts, severe depression, financial and professional stress, and statements to friends-points to suicide as the most likely explanation. This emerging consensus has led many scholars to see Lewis's story as both a tale of extraordinary achievement in exploration and science and a reminder of the personal and psychological costs carried by some early American leaders.

Read about Lewis's beloved dog Seaman.

Test your knowledge. Take the Meriwether Lewis quiz.

Updated: February 3, 2026