History & Prehistory

Jumping Buffalo: Pishkuns

Updated: February 3, 2026

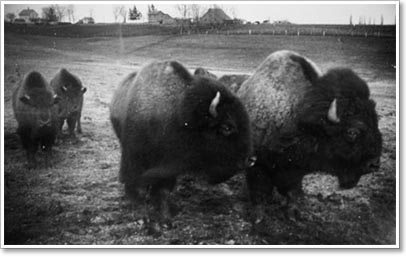

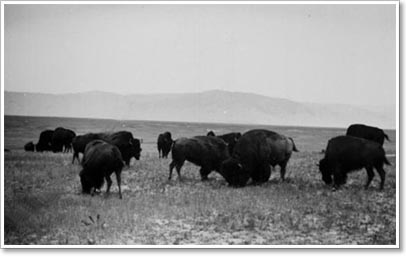

Plains Indigenous peoples have used buffalo jumps, or pishkun, for far longer than once thought, with archaeological evidence in the Northern Plains showing organized cliff-kill hunting systems in place for at least 2,000 years and in some areas several thousand years more. Instead of relying only on chance encounters, these communities developed detailed knowledge of bison behavior and landscape features, turning natural cliffs into carefully planned hunting sites that could provide food, hides, and tools for large groups. Studies of prehistoric bison ecology now suggest that in early historic times roughly 30 million bison lived in the Plains ecosystem alone, with additional herds elsewhere in North America, forming a vast, dynamic population that sustained many different cultures.

Blackfoot oral traditions, like the story of the first "buffalo caller" using a robe to draw animals closer, remain central to understanding how people remember the origins of pishkun hunting. Archaeologists and historians think that, alongside such key moments, communities experimented with many techniques over generations, gradually learning how to move herds, read the wind, and position people so that bison could be guided safely-or fatally-across specific stretches of prairie. Over time, buffalo calling and related ceremonies became specialized skills, often tied to spiritual visions and responsibilities, while the physical pishkun sites evolved from simple corrals into complex systems that combined drive lines, cairns, ambush points, and camping areas near reliable water and grazing. In Blackfoot, pishkun is often translated as "deep blood kettle," a reminder of both the scale of these hunts and their sacred importance within Blackfoot and related cultures.

In places that are now part of Montana, long-eroded stream channels created sandstone and limestone rimrock cliffs 20 to 50 feet high, with edges that can be hard to see until one is almost on top of them. Archaeological work at sites such as First Peoples Buffalo Jump and Madison Buffalo Jump has documented drive lines made from rows of stones, rock cairns, and other markers stretching for miles across the prairie, forming wide funnels that led herds toward specific drop-offs. During a hunt, people stationed along these drive lines waved hides, shouted, or used brush and scarecrows to keep the animals moving, while a highly skilled "buffalo runner," sometimes wearing a hide and imitating calf calls, lured the front of the herd onto the hidden brink before escaping to a safe ledge below. Once the first animals went over the edge, the strong herd instinct and pressure from those behind meant that dozens or even hundreds of bison could follow, piling up below the cliff.

Excavations at Montana jump sites reveal deep layers of bones and tools that show how thoroughly each animal was used. Below cliffs like those at First Peoples Buffalo Jump, archaeologists have recorded bone beds up to 13-15 feet thick, along with butchered skulls, broken limb bones, stone knives, scrapers, and hearths, evidence that people spent days or weeks there skinning animals, cutting meat for drying, and preparing hides. Ethnographic accounts and experimental work suggest that a single tipi might require a dozen large hides, and a successful jump could provide not only meat and shelter materials, but also sinew, bone for tools, and dung for fuel. Because blood, bone, and smoke scents lingered, many communities observed periods of ritual and practical "rest" for a site, waiting until rain, snow, and wind had washed away the smell of death or until grass regrew if fire had been used as part of the drive. Modern surveys indicate that more than 300 buffalo kill and jump sites are known within present-day Montana, and many individual jumps show evidence of repeated use over centuries or even millennia.

The labor needed to plan and carry out a pishkun hunt meant that families and bands often coordinated across wide areas. Archaeological and historical research at sites in and around Montana shows overlapping use by many nations-including Blackfoot-speaking peoples, such as the Siksika, Kainai (Blood), and Amskapi Piikani (South Piegan), as well as other Plains groups who came to hunt and trade. Scholars now emphasize that these buffalo economies were part of large trade networks that connected the Northern Plains to regions far to the south, where communities growing maize, beans, and other crops exchanged foods and goods with bison hunters. This combination of Indigenous oral history and ongoing archaeological work continues to refine our understanding of pishkuns as both ingenious hunting technologies and important spiritual and social centers in Plains life.

Test your knowledge. Take the pishkun quiz!

Updated: February 3, 2026

Updated: February 19, 2026