They Settled in Montana: The Homesteaders

Updated: February 5, 2026

On March 10, 1913 Charlie Russell, the famous cowboy artist from Great Falls, wrote to his friend:

"Bob you wouldent know the town or the country either it's all grass side down now. Wher once you rode circle and I night wrangled, a gopher couldn't graze now. The boosters say it's a better country than it ever was but it looks like hell to me I liked it better when it belonged to God it sure was his country when we knew it."

Charlie was upset because the open prairie he had known as a young cowboy was quickly turning into fenced farms and overgrazed pastures. "Boosters" were business leaders, land agents, and railroad promoters who bragged about Montana and tried to convince people to move there, often making the land sound easier to farm than it really was.

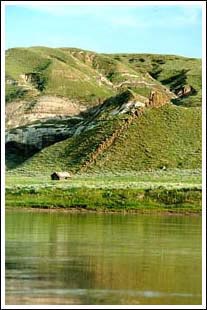

So why did Charlie Russell think the land was in such bad shape, and who were these "boosters" anyway? Today, historians and scientists agree that the high plains of Montana are a dry grassland ecosystem that can be damaged if too many animals graze or if too much land is plowed up. The Desert Land Act and later homestead laws opened the way for ranchers and settlers to claim and fence large areas where there had once been open, shared range. Montana's native bluebunch wheatgrass is nutritious and fairly tough in drought, but even this hardy grass cannot survive heavy use year after year. The land could not support the level of overgrazing and plowing that happened during the boom years, even though at first the prairie had seemed endless and unbreakable.

At the end of World War I, the U.S. government and many farm experts urged people to buy more machinery, buy more land, and plant more crops to feed a hungry world. European farmlands had been torn up by fighting, so leaders expected a long-term demand for wheat and other grains. James J. Hill, the "Empire Builder," had finished putting together the Great Northern Railway across northern Montana, and his company wanted to ship more people and more crops between the eastern and western United States. Hill and other boosters advertised Montana's "rainfall" and soil in glowing terms and sometimes used special demonstration farms that did better than the average homestead to attract settlers.

The problem was that the end of World War I happened at almost the same time that a long dry period began on the plains. From about 1909 to 1917, eastern and central Montana had several wetter-than-normal years, which made crops look great and encouraged thousands of homesteaders to come. After 1917, the climate shifted back toward the region's usual drier conditions, and repeated droughts plus poor farming practices made the 1920s very hard for farmers and ranchers. Farmers planted big but harvested little; ranchers began losing cattle by the thousands as pastures and hay fields failed.

Meanwhile, Jim Hill had been holding contests. He offered $1,000 for the best exhibits of grain and corn grown on "dry land" within 25 miles of his railroad line, then took these prize displays east to show how well Montana wheat could grow. He also offered cheap one-way "settlers fares" of $12.50 from St. Paul and Minneapolis to Bainville, Culbertson, and other towns in eastern Montana, which were big discounts even at that time. These tactics helped convince many families to invest their life savings in Montana land and equipment. When settlers stepped onto the railway platform, however, they often faced a confusing new world.

"Locators" waited at train stations to show the new settlers, or "honyockers," a piece of land nearby. For about 20 to 50 dollars, a locator would load a family into his wagon and drive them out of town to public land available for homesteading. Some locators were honest and truly tried to match people with good land and help them file the correct papers. Others worked closely with real-estate agents, banks, or big ranchers. They might point out poor land and claim that all the best homesteads were gone, then try to pressure settlers into buying more expensive private land instead. Many families also took out large bank loans for land, tools, and livestock, not realizing how risky this would be if crop prices or rainfall dropped. Banks and dealers were often willing to loan money because, if the farmer failed, the lender could repossess the land and resell it.

By all accounts, life on the homestead was hard. Imagine coming to Montana around 1910 or 1915, during the last years of the big homestead boom. First you had to travel a long distance by train or wagon, which cost money and took days or weeks. Then you had to find good acreage to claim, preferably with a reliable water source like a creek, spring, or well site. On the northern plains, land without dependable water was not very useful for crops or livestock. Once you had staked your claim, you had to build a shelter quickly before winter. If lumber was scarce, you might build a sod house from blocks of thick grass and soil. With luck you could call on neighbors, relatives, or church members to help, but many homesteaders found themselves working mostly alone.

The men and women who settled the West worked all day, almost every day, to survive. They planted crops, chopped wood, made candles and soap, built furniture, hunted and butchered animals, and repaired tools and buildings. They rose with the sun and often went to bed only after finishing chores by lamplight. Women might twist bundles of dried grass or cow chips to make fuel for the stove while rocking a baby with one foot. In the morning they milked cows, separated cream, and churned butter if they were lucky enough to own dairy animals. Children worked too, from an early age, feeding chickens, hauling water, gathering eggs, herding cattle, or watching younger siblings. Building a house was only the beginning; communities also had to organize schools, churches, roads, and volunteer fire crews to fight prairie fires.

Today, historians also stress that most homesteaders were settling on land that had belonged to Indigenous nations for countless generations. The Aaniiih (Gros Ventre), Assiniboine, Crow, Northern Cheyenne, Sioux (Lakota and Dakota), and other Native peoples had already shaped and cared for these prairies through hunting, burning, and seasonal travel. Long before homesteaders arrived, U.S. policies and military force had pushed many Native families onto reservations and broken up their homelands. Homesteading usually came after treaties and allotment laws had opened "surplus" reservation land to non-Native settlement, which caused more land loss for tribal communities.

From 1919 to 1920, drought and low prices hit Montana farmers hard. One famous example describes grain yields dropping from about 25 bushels per acre in good years to only a few bushels per acre on many dryland farms during the worst years. In some areas, the native grasses dried up after repeated overgrazing and plowing, leaving loose soil that blew away in the wind. Starving livestock died in the open or were sold for very low prices, and many ranchers could not repay their debts. Banks failed, and some communities lost stores and businesses when customers moved away or went broke. In those days, programs like federal welfare, Social Security, and Medicare either did not exist yet or were just being developed, so organized government help was very limited. Private groups such as churches and charities tried to help, but they could not reach everyone.

Between the early 1920s and mid-1920s, thousands of people left Montana's drought-stricken homestead regions. Historians estimate that about 2 million acres of farmland were abandoned and that roughly 11,000 farms-about one-fifth of all farms in the state-went out of business during this bust. Many families packed what they could into wagons or old cars and moved to cities or to other states, living "from hand to mouth" as they searched for work. Some of the damaged land has slowly recovered, but in certain places erosion, invasive weeds, and loss of deep topsoil are still visible more than a century later.

The original article mentioned workers on a dam near the Yellowstone River finding scorpions in the gravel and calling them the first scorpions ever seen in Montana. Modern biologists now know that small scorpion species live naturally in parts of Montana's dry badlands and rocky breaks. It is more likely that people simply started noticing these animals in new places because construction work disturbed the soil, rather than scorpions suddenly "invading" the state.

For a long time, people blamed all the trouble of the 1920s on "unusual climate conditions." Today, climate scientists who study tree rings and long-term weather records have found that the Northern Great Plains have always gone through cycles of wet and dry decades. The homestead boom happened during an unusually wet period, which misled many settlers into thinking that kind of rainfall would last forever. The drought that followed was harsh but not unheard of for this region; the truly unusual thing was that so much land had been plowed and so many cattle were grazing it at once. The combination of normal drought cycles with over-plowing, overgrazing, and poor soil protection created a human-made disaster.

As people settled into the West and less unclaimed land was available, homesteading acts were gradually replaced or repealed. New laws that focused on shared access and management of public lands took the place of earlier acts that simply gave land away. In 1928, Congress helped create the Mizpah-Pumpkin Creek Grazing Association in southeastern Montana, often described as the first cooperative grazing association in the United States. This association pooled public, railroad, state, and private lands into one large block and set rules for how local ranchers could share the range. The goal was to prevent overgrazing by spreading cattle across a larger area instead of crowding them into small, fragile pastures. Observers saw that land inside the association generally stayed in better condition than nearby overused range, which helped inspire broader reforms.

The Mizpah-Pumpkin Creek Association was just an experiment, but it led to bigger changes. In 1934, six years later, Congress passed the Taylor Grazing Act. This law created a system of grazing districts and permits on remaining federal public lands all across the West. Ranchers could still use public rangeland, but now they had to follow rules about how many animals they could graze and when they could graze them. The main idea was to reduce range wars, stop the worst overgrazing, and create a more fair and organized system for everyone.

Today, farmers and ranchers in Montana still rely on the land, but they use more scientific knowledge than homesteaders had. Agriculture remains one of Montana's most important industries, with major products including wheat, barley, beef cattle, hay, and pulse crops such as lentils and peas. There are now about 27,000 farms and ranches in the state, and the average operation covers just over 2,100 acres-much larger than a typical homestead, but somewhat smaller than the 2,714-acre average once estimated in the 1990s. Livestock still outnumber people in Montana, and there are nearly three times as many cattle as residents, depending on the year. About two-thirds of Montana's land area is still used for farming and ranching.

Science and cooperation are helping Montanans use more sustainable agricultural techniques than were common in the early 1900s. Researchers at Montana State University and other institutions use tools like radio or GPS collars to track cattle movements, so they can see which parts of a pasture cows prefer and which areas are being overused or ignored. Ranchers sometimes place salt blocks, water tanks, or special feed supplements, such as molasses tubs, in underused spots to encourage animals to spread out more evenly instead of grazing only near streams or gates. By learning which kinds of land different animals prefer, ranchers can guide herds in more natural ways and reduce stress on fragile grasslands.

Farmers are also working with scientists and conservation programs to protect soil and water while still earning a living. Crop rotations, cover crops, and reduced-tillage systems help keep plant cover on fields, protect soil structure, and keep nutrients in balance. Certain crop combinations can reduce salt build-up (saline seep), help manage pests, and improve soil health without relying only on chemicals. Wind-strip planting patterns and shelterbelts (rows of trees or shrubs) can slow the wind and cut down on dust storms.

Between 1982 and 1992, the federal Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) paid landowners to plant grass or other permanent cover on highly erodible farmland instead of plowing it, and this program helped Montana cut soil loss by tens of millions of tons per year. Projects across the state now also focus on keeping fertilizers and pesticides out of rivers and streams and on fencing or managing livestock around sensitive creeks and wetlands. These efforts help communities, wildlife, and downstream users share clean water.

Many of John Wesley Powell's 19th-century predictions-that dry western lands would need larger farm sizes, careful irrigation, and cooperative management-turned out to be largely accurate. Despite the broken promises and painful failures of the homestead era, Montana continues to produce high-quality livestock, wheat, and other crops that feed people around the world. Historians, scientists, and tribal leaders now use the story of Montana homesteading to teach how important it is to understand climate, respect Indigenous homelands, and care for soil and water when people build new lives in a challenging landscape.

Test your knowledge. Take the Homesteaders quiz.

Updated: February 5, 2026