Jumping Buffalo: Pishkuns

Updated: August 6, 2020

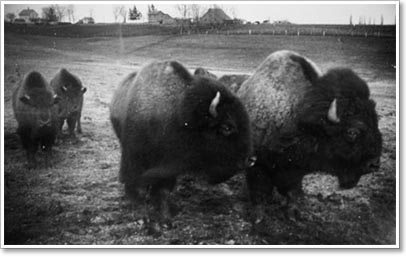

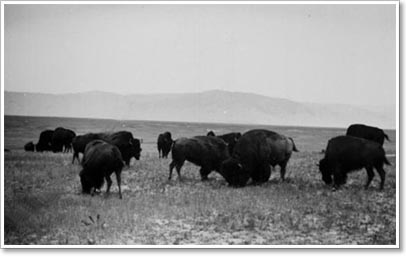

Plains Indians began using the "buffalo jump" or pishkun over 2,000 years ago. No one knows exactly how the tradition began or quite how the jumps were conducted. American Plains Buffalo (Bison bison) and their larger ancestors roamed the North American plains for thousands of years before native people began hunting large numbers of them. Researchers estimate that thirty to forty million or more buffalo once roamed freely from Texas to Canada and across the Mississippi River. Early hunts often were conducted in the winter season when Indians could herd the buffalo onto snowy fields, making it difficult for the large animals to run away. Still, those ancient hunters relied largely on luck to locate and trap the buffalo.

Blackfoot legend holds that a hunter was once out amongst a small herd of buffalo when black flies began bothering him. The hunter took up his buffalo robe and shook it like a dusty carpet in order to disperse the flies. Soon he noticed a few of the nearby buffalo walking toward him. He quickly ducked behind some trees and shook his robe again. This time, even more of the animals rushed toward him. In fact, the hunter narrowly avoided a stampede before returning to his camp. Upon hearing his story, some of the men in his camp built an early type of pishkun; a large corral made from logs. They asked the hunter to lure a few buffalo into this corral so that they could shoot their arrows at an easy target. The robe was shaken, the buffalo came, and the first "buffalo caller" was born.

Some historians believe that developing the pishkuns probably took more than just one simple act of waving a buffalo robe. More likely, people experimented for generations trying to discover ways of herding buffalo. But one chance encounter could have sparked a whole chain of events. The actual process may have been similar to that described by the Blackfoot legend. In time, "buffalo calling," the method for guiding buffalo herds, was considered a sacred art form practiced only by those who had received certain spiritual visions. Surely the technique developed with each hunt. The actual pishkun itself evolved over time as well, from crude corrals to strategic cliffs near good camping grounds. Pishkun, in Blackfoot, means something like "deep blood kettle."

Where large streams once ran down off the mountains and onto the Great Plains thousands or even millions of years ago, they cut out and formed rimrock cliffs. These cliffs generally range from around twenty to fifty feet high. Until you are right on the edge, it is difficult to tell that the cliffs are there at all. This is one reason that the ancient hunters could trick the buffalo into stampeding over the rock face; the buffalo couldn't see what was coming.

Indians constructed long rock walls to guide the buffalo toward the cliffs. These "drivelines" were short, maybe a foot or two high, but they were up to several miles long. Behind the drivelines, other hunters waited to be sure that no buffalo escaped. Disguised as a buffalo or another large animal, a "buffalo runner" would attract the attention of the herd and lead the buffalo toward the edge. The runner then jumped over, finding a safe place to wait just below the cliff's edge while the herd plunged to its death. The buffalo posses such a strong herd instinct that once they began dropping over the edge it was almost impossible to stop them.

After the herd had been "jumped," hunters prowled below the cliffs finishing off animals that hadn't died in the fall. Women worked hard all day long gathering hides, meat, and other useful parts from the buffalo. It took twelve hides to make a single tipi fourteen feet in diameter. Meat not collected by nightfall and dried or smoked would be rotten by morning.

It took a lot of hard work to make the buffalo hunt a success, but a successful hunt was then cause for great celebration and feasting. Several months would pass before the winds and the rains could wash away the scent of blood from below the cliffs. During that time of purification, a jump could not be used. Buffalo would smell the recent death lingering in the air. If one jump had been made in summer, another could be made during the winter. Fire was sometimes used as a driveline. In that case, Indians had to wait for the grass to grow back before using the jump site again. Once, there were over 300 jump sites in Montana alone.

Because the pishkun required so many men and women to hunt and process the buffalo, loosely connected tribes began to band together in order to carry out the hunt. For example, the Indian group we know refer to as the Blackfoot includes the Northern Blackfoot (Siksika), the Blood (Kainah), and the Piegan. It is thought that ancient hunting rituals and the practice of jumping buffalo brought some unity to these tribes. It is also believed that the North American plains Indians, particularly Apache and Comanche, also traded buffalo hides, meat, and other products with Meso-American Indians who were raising such crops as beans or maize.

Updated: August 6, 2020