They Settled in Montana: The Act

Updated: August 4, 2020

The Free Homestead Act of 1862 entitled anyone who filed to a quarter-section of land (160 acres) provided that person "proved up" the land. "Proving up" meant living on the land for five years. Otherwise, after living on the land for six months, homesteaders could choose to buy it outright for $1.25 per acre. Each homesteader was also assessed a $10.00 filing fee. Several hundred miles east of Montana, where the average rainfall is much higher, 160 acres was plenty of land to support a family and produce an abundance of crops. But in Montana, especially in eastern Montana where we have an arid climate, crops do not grow well without irrigation. On high desert-like plateaus, it can be difficult to find water for irrigation. The same 160 acres which will produce abundant crops in places like Kansas or Nebraska, falls far short of the 2,560-acre mark drawn by John Wesley Powell. However, new seed varieties and farming techniques known as "dryland farming" eventually helped eastern Montana to yield some of the best wheat in the entire country—for awhile.

After the Free Homestead Act was enacted people rushed to stake out their claims. But they didn't really rush to Montana at first. The 100th meridian, which runs through Nebraska, was considered the farthest point west where people could still farm without irrigation. Soon, lands east of the 100th meridian were filling up. Slowly, settlers began drifting into places like Montana, Wyoming, and Utah.

Montana's first Homestead entry was made by a woman in 1868 on the outskirts of Helena, the present-day capital. The first person to cultivate grain in the state was the Jesuit Father Desmet. DeSmet grew grain to supply his mission in the Bitterroot Valley and to teach agriculture to the local Indian population. As the dry western states began receiving more and more homesteaders, it became clear that John Wesley Powell had been right. 160 acres couldn't support much but a couple cows and a small garden; certainly not enough to make a living on.

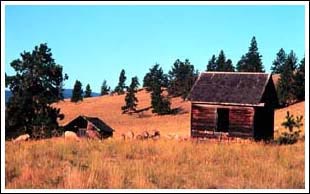

So in 1877 Congress passed the Desert Land Act. This act gave 640 acres (four times what the Free Homestead Act allowed) to any claimant who irrigated the land within three years. The person had to pay 25 cents per acre up front and an additional $1.00 per acre after they'd done the irrigation work. This act appealed to cattle companies and many companies moved in or started up. These companies would often pay men to claim the land. In turn, the company built him a small cabin and irrigated the place. After three years the claimant then transferred title to the land into that company's name.

In the first four years of this act 370 desert claim filings were made in Montana Territory covering 122,000 acres. In that same time, 608 homestead entries were made totaling just 93,671 acres. The idea behind the Desert Land Act was to "reclaim" some western lands not considered suitable for settlement. Ranchers often had small orchards, a nice garden, and few chickens to sustain themselves. We know now that this act contributed to overgrazing and a change in native vegetation. If excessive cattle speculation hadn't occurred, The Desert Land Act may have proved to be the best public lands model for the West.

Congress passed the Enlarged Homestead Act in 1909 . This act raised the amount of land deeded to each homesteader from 160 acres to 320 acres. Also, it was required that 1/8 of the land be continuously cultivated for agricultural crops other than native grasses. Now, Montana's weather tends to come in cycles. We might receive ten or twenty years of wet weather, followed by ten or twenty years of dry weather. It just so happened that 1909 fell during a wet cycle. As soon as more free land was available and prospects looked good for farming, the first wave of "honyockers" flowed into Montana.

Three years later, in 1912, Congress dropped the "proving up" time from five years to three years. More than 80,000 homesteaders moved into Montana between 1909 and the early 1920's. By the late 1920's, 60,000 of them had either packed up and left or were sent off to fight in World War I. Both farmers and ranchers had exploited the land during the wet years. They’d overgrazed, overfarmed, and spread themselves too thin. Banks sprang up and new counties were formed almost on a whim. No one realized that when the rains subsided, all that free land would come back to haunt them.

Updated: August 4, 2020