Facts & Figures • State Symbols

Updated: February 2, 2026

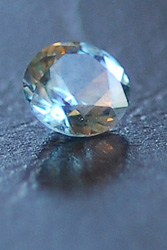

State Gemstones: Sapphire and Agate

Learn how Montana’s sparkling sapphires and patterned agates became official state gemstones.

Two Official State Gemstones

Montana sapphires and Montana agates have shared honors as the state's official gemstones since 1969, when the legislature passed a law naming both stones as state gemstones.

Recognition was a long time in coming. A century earlier, the small multi‑colored sapphires angered early placer miners by clogging gold sluices in places such as El Dorado Bar east of Helena. “Sapphire Collins” walked the streets of Helena in the 1860s with a pocket full of pretty stones. When he tried to convince local merchants and bankers of their value, he was told that gold was what mattered and that anything else was worth little.

Sapphires in the Treasure State

Eastern and European financiers were not as shortsighted. When they learned of Montana's sapphires in the early 1890s, substantial companies from as far away as London invested in mines across the state.

On Quartz and Rock Creeks west of Philipsburg, on Brown's Gulch and Dry Cottonwood Creek east of Anaconda, and along the Missouri River at El Dorado Bar, French Bar, Magpie Gulch, Metropolitan Bar, and other sites, a sapphire rush began.

The biggest sapphire excitement, however, came at Yogo Gulch in central Montana’s Judith Basin.

Yogo Sapphires

Jake Hoover, a friend of cowboy artist Charles Russell, made one of the earliest discoveries of Yogo sapphires while looking for gold in the gravels of Yogo Creek in 1895–1896.

The Yogo mines attracted wide attention and investment, and the U.S. Geological Survey once called the deposit “America’s most important gem location.” For nearly thirty years, British interests controlled much of the property, helping explain why the beautiful “cornflower‑blue” Yogos appear in royal and high‑end European jewelry collections.

Yogo sapphires are prized because they are naturally colored, usually need no heat treatment, and show a rich blue that keeps its brilliance under artificial light, unlike some sapphires from other parts of the world that can look darker or dull indoors.

From the late 1800s through the 1990s, the Yogo deposit produced many millions of carats of rough that may have yielded hundreds of thousands of carats of cut stones. Mining at Yogo has started and stopped many times, but modern companies have continued to redevelop the claims and report new production of rough and cut Yogos for the jewelry market.

The largest known faceted Yogo sapphire is a 10.2‑carat stone in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., cut from an unusually large piece of rough discovered in the early 1900s.

Montana Agate

Montana's Council of Rock and Mineral Clubs supported not only the sapphire for gemstone honors, but also asked for equal recognition for the exquisite and ever‑varying Montana agate, found in abundance along the Yellowstone River and its tributaries in eastern and southeastern Montana.

Montana agate (often called Montana moss agate) is a distinctive form of cryptocrystalline quartz, usually translucent white to pale gray with intricate black, brown, or red “mossy” patterns and banding created by iron and manganese oxides.

These agates formed in volcanic rocks tens of millions of years ago and were later eroded and carried down the Yellowstone River. Today, rockhounds search gravel bars between Billings and Sidney to find them and turn them into polished cabochons, beads, and jewelry.

Cut and polished, both Montana sapphires and Montana agates are beautiful additions to jewelry and are much‑sought‑after gems.

What the Gems Represent

Between the sapphire and the agate, Montana's east and west, its mining heritage and rock‑hounding hobby, and its long geologic story are all represented.

Special acknowledgements: Montana Historical Society, Rex C. Meyers, and Norma B. Ashby.

Updated: February 2, 2026